LEBOHANG KGANYE

INTERVIEW

©Lebohang Kganye, Re palame tereneng e fosahetseng, from series Reconstruction of a Family, 2016.

Lebohang Kganye is an artist born in Johannesburg, South Africa, where she currently lives and works. While photography is her main medium, she often draws inspiration from theatre, performance and storytelling while working in the reconstruction of memories and stories told by her family. Since 2013, Kganye has been researching her family history and travelling through South Africa, interested in the stories and images she could uncover from her family album. Her artistic process derives from those oral narratives and photographs she collected on her travels, where her experimentation into fiction and performance begins.

"Ho Thubeha ha lebone" [A breakage of the light] (2016-ongoing) is a body of work that began as a historical journey originating through her Grandfather, who quickly became the central figure of her family's mythology and Kganye's fantastical oeuvre. As Kganye reframes and reenacts her family memories, she juxtaposes the information collected through her family album and stories that are orally passed on through generations, distinctively stressing an unreliable aspect of photography and memory itself. And, by doing so, the artist sheds light into the process of constructing narratives through vernacular photography while also telling us something about the collective memory of a distinctive period of time, the apartheid.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with the artists involved in the 'Pass it on. Private Stories, Public Histories' exhibition held at FOTODOK in 2020, curated by Daria Turminas, which can be viewed virtually here. This exhibition explores the constructed nature of memory, the complexity of its production and transmission processes. By presenting ongoing projects, it urges the viewers to question their relationship with archives, their content and possible meanings.

Archivo Platform (AP) | The work "Ho thubeha ha lebone" [A breakage of the light], presented at FOTODOK's exhibition, Pass it on. Private Stories, Public Histories, deals with an exploration of your family's history through examining photographic albums and collecting oral stories from family members. By using these images as cut-out forms detached from the traditional photographic frame, you gain the possibility of combining and recombining them in an endless game. By doing so, you are not only approaching those stories, you are reframing them as well. Could you explain how this experience shaped your perception of memory?

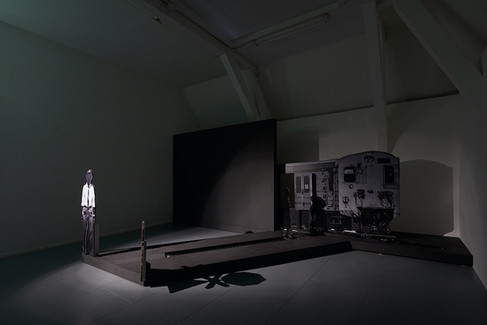

Lebohang Kganye (LK) | "Ho thubeha ha lebone" considers the act of remembering and the construction of memories through photography. By constructing a visual narrative through the use of life-size flat-mannequins of the characters related to me in various family stories to explore the materiality of memory and memories as a field of invention. In my creative practice, photography is used as a way to recreate moments that I have never myself experienced. The cut-outs are used as a tool in the (re)construction of collective memory.

Lebohang Kganye, Ho thubeha ha lebone [A breakage of the light], 2016-ongoing.

‘Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories' at FOTODOK, 27.11.20-28.02.21 © Studio Hans Wilschut

AP | The subject of the family has been present in your work for the last past years. How did the family album become a research object in your practice, and, as an artist, how do you deal with the personal or emotional attachment to such images?

LK | My photographic journey seems to be a deep response to loss and mourning – not just of different individuals, but of history, language and oral culture. By deconstructing photo albums and memory’s proximity to fantasy, I explore the act of remembering and commemorating through a (re) imagined personal archive. As I went through the family albums I came to realise that the photographs were more than just a memory of moments or people who have passed on, or reassurance of an existence, but that they were a constructed life.

AP | You seem to highlight the figure of your grandfather, not only through the photographs in which he appears, as in "Ho thubeha ha lebone" (2020) [A breakage of the light] but also in the way you impersonate him, as in "Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story" (2013). However, you've never had the opportunity to meet him as he passed away before you were born. It is as if you only got to know him through the stories and the images your family shared, which leads to an interesting quality of fiction in your work, wouldn't you agree?

LK | "Ho thubeha ha lebone" (2020) similar to "Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story" (2013) testifies to degrees of absences in that I did not know my grandfather any better than my own father, but yet feel the need to identify with him while ascribing a level of rejection to my own father. Both works explore the human need to retain and the very construct of memory - we fill in those gaps and reconstruct our memories.

©Lebohang Kganye, The Suit, from series Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story, 2013.

[left] ©Lebohang Kganye, Last Supper, from series Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story, 2013.

[right] ©Lebohang Kganye, The Alarm, from series Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story, 2013.

AP | These memories paired with images passed down to you from your family have altered over time. Do you think the artistic strategies you use contribute for a halt of memory? By creating these scenes in which memories overlap, are you trying to communicate the dissociation of truth in memory, thus highlighting the family photo album as an image-based performance socially and culturally constructed?

LK | As I went through the photo albums I came to realise that the photographs were more than just a memory of moments or people who have passed on, or reassurance of an existence, but that they were a constructed life. Photographer and therapist Rosy Martin suggests that with regard to family albums, “It seems that in most families mothers are the archivists and guardians of family history, selecting what shall be remembered, what forgotten; constructing a mythology which validates their own ‘good mothering’.” (Spence and Holland 1992: 1) This statement rang true with my own personal situation and my work diverted into different threads which explored the personal and collective histories of my family, these being the story of my mother, my grandfather, clan names and my own story.

AP | While exploring your family's memories, you question not only the images from the family album but also the stories you've been told about them. Could you elaborate on this connection between shared memories, imagination, fiction and performance in your work?

LK | Photography is a medium that relies on the management of light, dark and all the tonalities in between, with my body of works in “Ke Lefa Laka” (2013) this process which is often constrained by traditional methods was artistically altered. It is in this interference or editing of the image that shift our perception of the idea of truth. The power of one’s own experience supersedes the notion of fact. The facts become negotiable and a whole plethora of possibilities and alternative are created.

[left] ©Lebohang Kganye, Ka mose wa malomo kwana

[middle] ©Lebohang Kganye, Kwana Germiston bosiu II

[right] ©Lebohang Kganye, Ke le motle ka bulumase le bodisi II

From series Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story, 2016.

AP | Works such as "Reconstruction of a family" (2016) and "Ho thubeha ha lebone" [A breakage of the light] deal with a deconstruction of society's preconceived notions of family. By appropriating images from your family album, you unveil stories behind the images and thus dismantle a certain idea of the family ideal represented through photo albums. Could you share any discoveries you made beyond the surface of the family pictures?

LK | I chronicle my family name using various modes of presentation and archival materials in the form of family albums, interviews with individuals involved to weave family narratives that would otherwise not have a platform or form beyond the experiential. Both methods of data collection lead one to an approximate truth. An individual memory about a particular event may include political and personal bias. On the other raw artifacts such as photographs have the inherent limitation of speaking to context. Both these flaws open up an opportunity to generate my mythology and fluid storytelling.

[left] ©Lebohang Kganye, O emetse mahala, from series Reconstruction of a Family, 2016.

[right] ©Lebohang Kganye, O robetse a ntse a bala Bona, from series Reconstruction of a Family, 2016.

AP | By working with personal imagery at the intersection of narrative, storytelling and memory, you create a performative gesture that doesn't stop at your own family's history but also tells us something about the collective memory of South Africa during apartheid. Would you care to comment on that?

LK | The photomontages became a substitute for the paucity of memory, a forged identification and imagined conversation. Toni Morrison, in The Site for Memory (1995: 91) states that, “The exercise is also critical for any person who is black, or who belongs to any marginalized category, for historically, we were seldom invited to participate in the discourse even when we were its topic”. Therefore, similarly, “I must trust my recollections. I must also depend on the recollections of others. Thus memory weighs heavily in what I write, in how I begin and in what I find to be significant”