PHOTOFILE | INTERVIEW

FROM THE ARMENIAN QUARTER

OF JERUSALEM

Photographic Documentation of

Armenian Orphans in 1922-1924

A CONVERSATION WITH DR. BORIS ADJEMIAN

Director of the AGBU Nubar Library, Paris

BY IDIL CETIN

Dr. Boris Adjemian is a historian specialising in the study of the Armenian diaspora and on the history and memory of migration and mass violence, and the editor-in-chief of the journal Études arméniennes contemporaines. Since 2013, Dr. Adjemian has been the director of the Nubar Library in Paris, one of the most important Armenian libraries in the diaspora. This interview focuses on the Nubar Library’s Jerusalem file, which contains, among other images, photographs of Armenian orphans who lived in the city between 1922 and 1924, and discusses the photographic documentation of the lives of the orphans and the subsequent archiving of these images as well as Dr. Adjemian’s research on the subject.

In 2017, you published an article with Talin Suciyan,[1] where you explored how the photographic documentation of the Armenian orphans in Jerusalem in the 1920s can be used as a source for the social history of the city’s Armenian community.[2] These orphans have not received much scholarly attention up to this day, not only despite such photographic documentation, but also despite the very physical traces they left behind, where they inscribed their names and places of origin on the walls of the orphanage, which are still visible today.[3] Could you start by describing how you became interested in this subject?

At an Armenian Studies Colloquium in Paris in 2008, I had given a presentation on my doctoral research on the Armenian diaspora in Ethiopia, where I had mentioned that the community had begun when the future emperor of Ethiopia, on his visit to Jerusalem in 1924, had called upon forty Armenian orphans to form the royal brass band.[4] I had met Kevork Hintlian [5] at that colloquium and it was then that we first discussed the possibility of me going to Jerusalem. I went there for the first time two years later and spent two weeks looking for traces of the orphans sent to Ethiopia, trying to find some archival documentation and perhaps hearing some oral testimony on the subject. During these two weeks, I had the opportunity to have in-depth conversations with Kevork, which helped me a lot to understand the cultural and religious context in which the Ethiopian-Armenian relationship developed. Thanks to him, I was also able to meet people with whom I could talk about the old days. Digin (Miss) Arshaluys Zakarian, for example, who lived in a flat near the Armenian convent and who was there when the orphans came to Jerusalem, was the only person who had a living memory of that period. She remembered not only the forty children who were sent to Ethiopia, but also the orphans who arrived in Jerusalem in 1922. All these conversations drew my attention to the issue of orphans more and more, but I could not find much at that time. I could not study the patriarchal archives, either, as they were inaccessible. But after that, I began to return to Jerusalem almost every year. I was interested in the issue of orphans from the perspective of the social history of Armenian Jerusalem. I was struck by the fact that the history of these orphans was almost non-existent, even though they were survivors of the genocide.[6] The matter was certainly not completely unknown, and I knew about it because Raymond Kévorkian and Vahé Tachjian had devoted a chapter to Jerusalem in their book on the history of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), in which they dealt with this history.[7] But there was no comprehensive study on the subject. Inside the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem, the fact that the past was very much alive in the present really amazed me. These visits to Jerusalem and long conversations with Kevork Hintlian also had an important impact on me personally. At that time, I was working as a secondary school teacher. It was with his encouragement to do something as a historian that I left teaching after my PhD, became the director of the AGBU Nubar Library in the end, and dedicated my professional activity to working as a historian of Armenian immigration, diaspora, and the genocide.

It sounds like your story as a historian is interwoven with your interest in the story of the orphans in Jerusalem. Could you tell us more about how these orphans ended up in Jerusalem?

The arrival of these orphans in Jerusalem is, of course, linked to the Armenian Genocide in 1915. According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople at the time, there were 200,000 orphans and young women at the end of the Genocide, half of whom lived in Armenian and Western orphanages while the other half lived with Muslim families. About 800 of these orphans, who were staying in a camp in Iraq and being looked after by the British, were decided to be brought to Jerusalem in 1922 in agreement with the AGBU. The AGBU established two orphanages for them in Jerusalem. One was the Araradian Orphanage inside the Armenian monastery, where the older boys lived, and the other was the Vasbouragan Orphanage inside the Greek monastery of the Holy Cross, where the girls and younger boys stayed. These orphans lived in Jerusalem for about two years. After 1924, they began to be sent to various places, but mainly to Soviet Armenia to rebuild an Armenian homeland in the Caucasus.

Photographic documentation of the orphans in Jerusalem began in 1922. Who took these photographs and for whom?

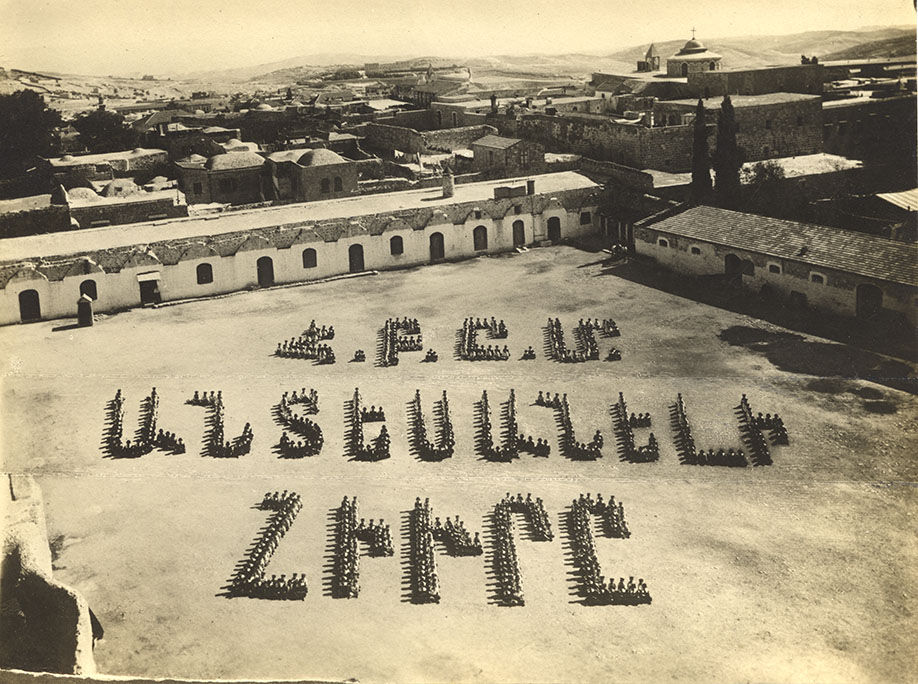

We are not always well informed about the photographs themselves, for instance about who took them. For some of them, we have the name of the photographer. Sometimes the photographer is someone well-established in the Armenian community in Palestine, such as J. Zerounian or Garabed Krikorian. In cases where the name of the photographer is unknown, it is still possible to comment that they were taken by professional photographers, hired by the AGBU. These documentations were made for people who financed their relief efforts to help the orphans. Many of these pictures were published in the AGBU publications of the time, such as the Mioutiun and Housharar, to give information about how these children were doing in the orphanages. The photographs showed them well dressed, training in workshops to learn trades, such as shoemaking or hat-making, and eating in the orderly refectories. They displayed that the genocide was now behind them and that they were being treated well. In some of these photographs, children were also lined up to write a message with their bodies. There was one photograph that I remember that struck you, as well. The children were photographed from a rooftop and were lined up to write a message in Armenian that read andesanali hiure (“the invisible guest”). Of course, we should look at these images from a transnational perspective. Although Armenians were at the forefront of philanthropic humanitarianism in the 1920s and 1930s, they were not the only ones making these kinds of photographs. The Near East Relief did something very similar for an American audience at the time, using images of Armenian refugees in their fundraising campaigns in the US.[8] However, these orderly images did not necessarily reflect the daily reality of the orphans. Obtaining food for the orphans, for example, was a major problem at the time. There were also occasional epidemics. But these aspects of the orphans’ lives were not photographed.

What about the archiving of these images? How did they find their way into the Nubar Library?

The decision to open the AGBU Nubar Library in Paris was taken in 1927. The library was already active in 1928 but was officially inaugurated in 1929. As the photographs were taken in the context of the AGBU’s relief efforts, it is not surprising at all that when the AGBU’s central library was set up in Paris, all the photographic documentation was transferred there. This is why we have all the originals. We also have the periodicals in which these images were published at the time. Many captions to the photographs were written down by Aram Andonian, the first librarian of this institution until 1951. Such photographic documentation of the orphans was carried out in many places at the time, all of which can be found in the Nubar Library. In fact, this documentation forms the core of our library’s photographic collection. We have similar files with even more photographs from Aleppo, Beirut, Damascus, Greece, and so on. However, the difference between these files and the Jerusalem file is striking because the latter contains not only photographs of orphans, but also images of the monastery, Armenian pilgrims and immigrants taken in the 19th century.[9] Jerusalem is an important city for the Armenians, who claim to have been there since time immemorial. As a result, the photographs of orphans stand side by side in this file with images of the monastery, displaying the life of the pre-war Armenian community in Jerusalem. All the other files we have regarding the orphans, on the other hand, focus only on the post-genocide period. This is what makes the Jerusalem file so special.

Could this be the explanation for the “invisible guest” writing in the photograph, as the orphans were staying in a place where there was already an established Armenian community, and it was clear from the start that they would only be living there for a short time?

Perhaps. Although there are similar images from other orphanages of children lined up to write messages, this is the only one with the “invisible guest” script. But we should also note that this was a common slogan of the humanitarian propaganda conducted by the Near East Relief in the US at the time. In order to help the starving orphans in the Middle East on the eve of Christmas, people were asked to have an invisible guest at their table and to spare some food for them. So, the writing in the Jerusalem picture was not an original creation of the photographers. But this time it was addressed to an Armenian audience, as it was written in Armenian.

As you mentioned, similar photographic documentations were made in other orphanages in other locations at the time. Could it be that the same orphans were photographed and rendered visible in many places, while their individual stories remained invisible in each case?

Yes, the orphans were very mobile. They had to change institutions all the time and they had to move between different countries. In the case of Jerusalem, although some of those who were old enough to leave the orphanage settled down there, the remaining orphans left the convent in 1924. It is, therefore, a possibility that they were photographed several times by the AGBU in different places, without any indication of the mobility they were experiencing. Or they may have been photographed by the Near East Relief, as well. It is, of course, difficult to identify the children in the pictures. But the names of the orphans sent to Soviet Armenia should be found in the Armenian National Archives. These records can be consulted to see where the orphans who went there previously lived.

What other documentation exists about these orphans and where are they today?

The daily correspondences between the AGBU head office and the various branches regarding the needs of the orphanages at the time are kept in the Nubar Library. The archives of the orphanages, on the other hand, are located in the AGBU branch in Cairo. There you can find the identity cards of all the orphans with their portraits on. In Paris, we only have a few samples of these. They may also have other photographic documentation in Cairo, and of course in Jerusalem, which probably more or less overlaps with the collections found in Paris.

Is it possible that any other Armenian library or research institution in the world has similar collections?

I do not know of any collection of this kind. Project SAVE[10] in the US has one of the most extensive photographic collections pertaining to Armenians, but theirs is very different from what we have in Paris.

I asked about this because I wondered if the general fragmented and dispersed nature of the archiving of the Armenian past, which is an effect of the genocide, was also replicated in these collections.

The fact that the Nubar Library has all the photographic documentation of the orphanages carried out by the AGBU does not mean that this documentation is not only a fragment of a larger ensemble that might have been scattered around the world. The library’s photographic collection also includes portraits that have nothing to do with the AGBU. These images are of course fragments of a larger body of photographs dispersed around the world. But this is the case with many Armenian institutions around the world, such as the collections of the Project SAVE or those virtually accessible on the internet thanks to the Houshamadyan project. However, we should bear in mind that these are gathered collections as much as scattered, as they have been built up with the donations of Armenians. The same is true for the portrait collections of the Nubar Library; the majority of our collection was also donated by Armenians. It is quite possible that some of the photographs that are now in various Armenian institutions around the world were once part of other ensembles before they were scattered around the world after the genocide, while many others were lost forever. In this sense, the portraits in our collections, as much as they are gathered, illustrate this dispersal. But they are also points of connection today, linking not only different Armenian institutions, but also Armenians as a whole.

[1] Talin Suciyan is a scholar in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. Her research interests include, among other things, the autochthonous populations of the Middle East, 19th- and 20th century Western Armenian and Armeno-Turkish literature and source studies as well as interdenomination relations and legal systems in the Ottoman Empire.

[2] See Boris Adjemian and Talin Suciyan, “Making space and community through memory: Orphans and Armenian Jerusalem in the Nubar Library’s photographic archive”, Études arméniennes contemporaines, 9, 2017: http://journals.openedition.org/eac/1129.

[3] The orphanage, which used to be Armenian monastery’s seminary school, is now the Edward and Helen Mardigian Museum of Armenian Art and Culture. The museum has rooms dedicated to the history of orphans in Jerusalem.

[4] This study was first published in French in 2013 (La fanfare du négus: les Arméniens en Éthiopie xixe-xxe, Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS). The publication of an English translation has just been released. See Boris Adjemian, The Brass Band of the King: Armenians in Ethiopia, London: I.B. TAURIS, August 2024.

[5] Kevork Hintlian is a community historian living in the Armenian quarter of Jerusalem.

[6] The Armenian Genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire, starting in 1915 and extending over to 1916, as a result of which over 1.5 million Armenians were massacred.

[7] See Raymond H. Kévorkian and Vahé Tachjian (eds), The Armenian General Benevolent Union: One Hundred Years of History, Cairo, Paris, New York: AGBU, 2006, p. 81. The Armenian General Benevolent Union was a philanthropic organisation founded in Cairo in 1906 initially to help Armenian peasants and to establish schools and orphanages in Western Armenia. After the genocide, the union turned all its attention to helping the survivors.

[8] The Near East Relief was founded in the USA in 1915 with the aim of assisting Armenian survivors of the genocide as well as Greeks, Assyrians and Arabs.

[9] The files can only be accessed within the premises of the Nubar Library.

[10] Project Save Photograph Archives is an institution founded in 1975 by Ruth Thomasian to preserve and share the photography of the Armenian global experience. The institution currently has a collection of over 80.000 photographs. See https://projectsave.org/

How to cite

Cetin, Idil. ‘FROM THE ARMENIAN QUARTER OF JERUSALEM: Photographic Documentation of Armenian Orphans in 1922-1924’. Archivo Photofile, 2 December 2024. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14258768.

About the author